This fall, I’m teaching an upper-level literature course on nineteenth century American women writers. It’s a big class, full of mostly English and Gender Studies majors and minors. This is the second time I’ve taught this course, but the first time I’ve included Ojibwe poet Jane Johnston Schoolcraft.

(Note: in the 19th century, the Ojibwe people were variously known as Chippewa, Ojibwe, and Anishinaabe. Anishinaabe is the name that is most in use now. Schoolcraft used the name “Ojibwe” to describe herself, so, following scholar Robert Dale Parker, that’s the word I’ll use too.)

Born in 1802, Schoolcraft (whose Ojibwe name was Bamewawagezhikaquay, or “Woman of the Sound the Stars Make Rushing through the Sky”) was one of a large métis (French for “mixed”) population in her hometown of Sault Ste. Marie, located on the border of the Michigan Territory and Canada. The daughter of an Irish immigrant and an Ojibwe mother; a bilingual speaker and poet; the métis wife of a white man, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, the first U.S. Indian Agent in the Michigan territory; highly educated and among Sault Ste. Marie’s social elite; possessing both Romantic and Ojibwe sensibilities; married to another literary writer but not publishing in her lifetime; writing within the poetic conventions of her time—Schoolcraft is a complex figure, and because of this I thought she’d be a great writer to begin the course. I wanted to get students thinking immediately about nineteenth century women as not easily categorized, to get them used to holding contradictions and complexities in their minds without trying to oversimplify these women’s lives or their art.

Robert Dale Parker’s excellent scholarly edition of Schoolcraft will give you everything you need to get going with this poet: a thorough and engaging introduction to her life and work; all of her known poems and prose; and extremely helpful notes on each poem that detail, as best as can be known, when it was written, in whose handwriting (Jane Johnston Schoolcraft’s or Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s) it was found, whether it is a translation, and if so, if it was translated by Jane or by Henry. Often, it’s not clear who wrote or translated what (something Parker does not gloss over but lets be, in all of its complexity).

I asked students to read all of the poems from the Parker edition for the next class period (but to focus on a handful of poems I wanted to make sure to cover in class discussion). Each day, I asked students to reread all the poems while focusing particularly on the poems we’d be discussing in class.

A three-day Schoolcraft plan

I had three days for Schoolcraft, though I wanted more. (Our terms are ten weeks long at my school, so pretty much every writer gets about three days, unless they’ve written an exceptionally long novel—looking at you, Harriet Beecher Stowe.) I tried some different strategies each day to shake things up—and also, since it was the start of the term, so students could quickly get used to the kinds of things I like to do in my courses. This term, I’m ditching the short weekly papers I usually assign in favor of daily informal writing: one or two paragraphs due each class (done mostly outside of class, but sometimes in class) which I am hoping are low-stakes enough to encourage students to play around more, make more of a mess, and take more risks with their ideas. In addition to daily writing, we are using a variety of multimedia, looking at other 19th c. texts and visual materials to provide context, and diving into literary criticism.

Day 1: The Way In

Writing focus: Personal response

Thematic focus: Nature

Poems discussed: “To the Pine,” “To the Miscodeed,” “On the Doric Rock, Lake Superior,” “Pensive Hours”

It makes sense to me to do a more personal writing assignment on the first day of a new writer, particularly with nineteenth century poetry, which may at first feel old-fashioned and off-putting to even the perkiest English major. I think it’s good to encourage students that any way into the poems they can find is a good way in, and that they don’t need to be intimidated by this poetry.

On the first day of class (the syllabus-introductions day), toward the end, I put the names of four Schoolcraft poems—none of which the students had read yet—on the board and asked students to choose one. Then I asked them a few simple questions, which I adapted from an exercise by Lynn Hammond that I first found in the always useful Engaging Ideas, by John Bean:

- Why did you choose this title over the other ones?

- What in this title would draw you into the poem—would make you want to read it? (Or conversely, is there anything in this title that causes resistance or makes you not want to read this poem?)

- Based on the title of the poem, what do you expect this poem to be about?

From here, I told students to keep what they had written and, for next time, to write about whether their expectations were met once they actually read the poem in question.

I learned that for many students, familiar nature imagery (pine trees) was the draw, although a few brave students made their choice based on their lack of familiarity with title words (like the miscodeed flower, also called “spring beauty”). Other students chose a poem set on Lake Superior because we are in Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula isn’t that far away from us. Many students were surprised at what “miscodeed” was (they guessed all kinds of things). Others were comforted by the simple fact that Schoolcraft felt such a connection to pine trees (as one student said, “I have a thing for pine trees”).

This first day on Schoolcraft, we talked about her as a Romantic poet and a nature poet, as well as how her métis identity and geographical region may have influenced her writing. I supplemented this lecture with lots of visuals: pictures of the miscodeed flower, 19th century maps of Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and photos of Lake Superior so students could get a visual sense of Schoolcraft’s relation to place.

Day 2: Form, Genre, Contexts

Writing focus: Annotation

Thematic focus: Motherhood

Formal focus: Elegy, child elegy

Poems discussed: “Elegy: On the death of my Son William Henry, at St. Mary’s,” “Sonnet,” “To my ever beloved and lamented son William Henry,” “Sweet Willy”

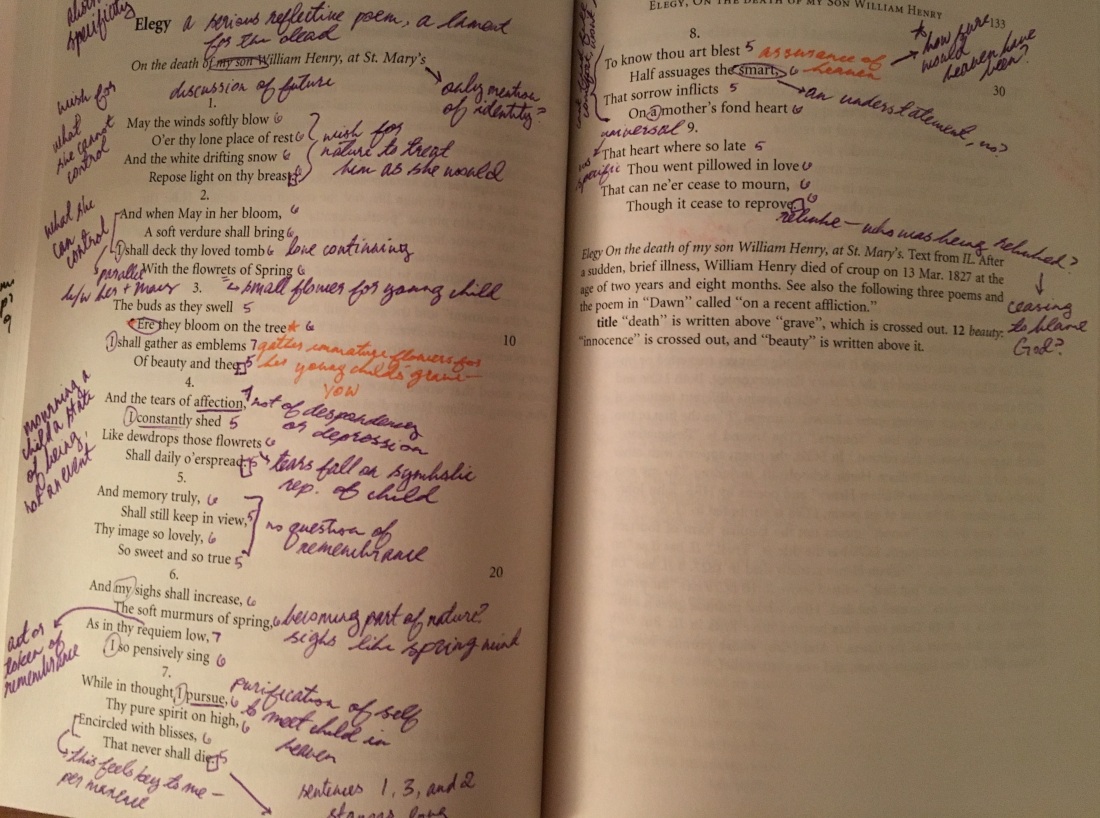

Our second day on Schoolcraft, we discussed her wrenching child elegies, written after the death of her oldest child, William Henry, from croup at the age of two. I wanted students to really dig into the poems’ formal qualities, so the informal writing assignment due in advance of this class was an annotation. Since Megan Ciesla has recently discussed annotation in detail on this site, I won’t say much more about this except try it—it’s old school, and that’s part of the fun for students. I, too, asked students to do the annotation by hand (either in their books or on a photocopy of a page if they don’t want to write in the book) and then take a photo and upload it. I printed them all out (speaking of old school) and then graded them by hand (my usual practice). There’s something really interesting in seeing where students will go when they’re not typing and not thinking “Essay! Must write essay!” I found that most of them uncovered much, much more about the poems’ formal qualities than they might have mentioned if I had had them write a few paragraphs of analysis instead. There was no opportunity for summary, so they had to jump right in and analyze.

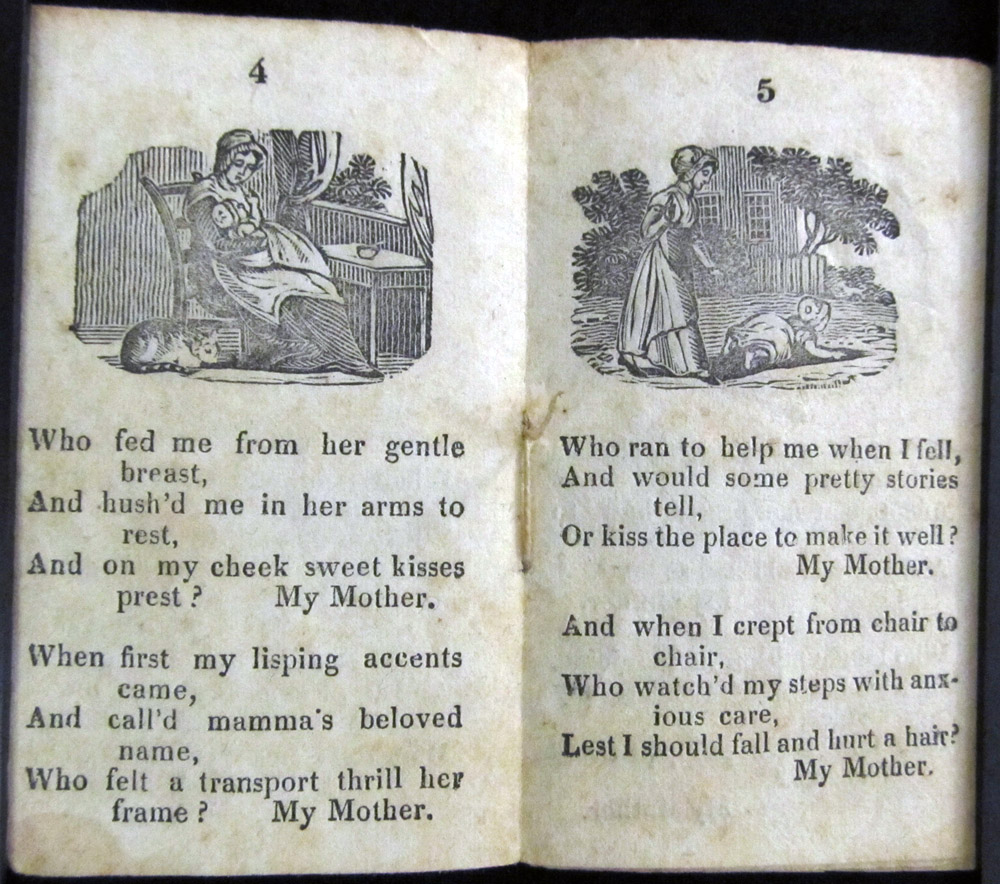

To give students context during class, I put up slides of other poets’ poems from the period: Lydia Sigourney’s “To a Dying Infant,” which allowed us to talk more about the child elegy genre of the period; and Ann Taylor’s “My Mother,” a poem that directly influenced the form of Schoolcraft’s poem “To my ever beloved and lamented Son William Henry.” Because students had thought so much about the craft of the poems in their annotations, they were better able to make connections between stylistic commonalities: similar imagery in Sigourney and Schoolcraft, for example, or similar use of refrains and questions in Taylor and Schoolcraft.

Day 3: Criticism, revision, and translation

Writing focus: Taking a position

Thematic focus: Identity, authenticity, ownership

Poems discussed: “Invocation,” “The Contrast,” “Song of the Okogis, or Frogs in Spring,” “On leaving my children John and Jane at School”

Like Corinna Cook, I also assign critical works in class, and I also have students in charge of leading class discussion on those critical works. In the past, these sessions have really fallen flat, but I was trusting to the power of daily informal writing to help us along this time around. Because the discussion-leading group would be outlining the larger points of the article with us, I decided to focus the informal writing assignment a bit more tightly. For this class, I asked students to choose one small point from the article they read (Bethany Schneider’s “Not for Citation: Jane Johnston Schoolcraft’s Synchronic Strategies”) and to make one of these argumentative moves with it: to say “No,” to say “Yes,” or to say “Maybe, but” (which I am again stealing from Bean! Y’all see what I was rereading this summer). Students then had to write 1-2 paragraphs explaining their response.

This article proved extremely difficult for students (it’s quite dense and complex), but that didn’t prove a deterrent to class discussion. I was surprised and thrilled that our class discussion on this article lasted nearly the whole class long (I had only budgeted for half the class, but students had so much to say that we just went with it). This is a big change from how these article discussions have gone in the past, and I attribute this directly to the targeted informal writing I had students do. They had taken a position on the article and they were ready to share those positions!

Much of Schneider’s article asks readers to consider the interplay between Schoolcraft’s poetry and the writing of others, whether that be husband’s translations of her poems, her own allusions to Romantic poets like Shelley and Keats, or her response to the language of letters she received from acquaintances. So the poems selected for this class were in multiple versions: multiple English versions all written by Schoolcraft; poems Schoolcraft wrote in Ojibwe and translated into English; poems Schoolcraft wrote in Ojibwe that were translated by others. It’s not always clear, as Parker makes evident in his wonderful notes and introduction, when an English translation is Jane’s and when it is Henry’s. Our discussion, then, revolved around what we perceive as “authentic,” which typically also involved questions of identity (i.e. how do we “read” Schoolcraft as a person, and how does this affect the way we read her poems? how do we read a Schoolcraft poem if we’re not totally sure she wrote or translated it?).

We spent a long time on the poem “On leaving my children John and Jane at School,” discussing (as Schneider also does) the differences between the three versions that are provided in Parker’s edition of Schoolcraft: Schoolcraft’s Ojibwe version, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s “free” English translation, or a contemporary translation by Dennis Jones, Heidi Stark, and James Vukelich. This is a perfect poem to talk about translation and authenticity. How does seeing these three versions on the page next to one another force us to compare versions and ultimately color our readings of all three versions? Do we believe that the literal version by modern scholars is the one Schoolcraft herself would have made had she chosen to translate this poem into English? Would Schoolcraft’s version have looked more like Henry’s, strictly rhymed and metered and adhering to the conventions of early 19th century poetry—since this is how she writes all of the rest of her English language poetry? Or is there something important (we thought that there was) about the fact that Schoolcraft never translated this particular poem into English?

To end our session on Schoolcraft, I played a recording of Margaret Noodin, an Anishinaabe poet and scholar who is the founder of ojibwe.net (an Anishinaabe language site with recordings of Anishinaabe songs and poems—an amazing resource), singing the Ojibwe version of “On leaving my children John and Jane at School.” Although no one in the class speaks Anishinaabe, we agreed that we were all moved by the beauty of the song. I liked ending the section on Schoolcraft in this way, with an acknowledgment that with any writer we read this term, there will be things we can’t access and can’t understand—but that makes these writers from another time more interesting, not less.

5 thoughts on “Teaching Jane Johnston Schoolcraft”